Yoga is Not A Workout

In my obesity reversal journey, there were many aha! moments.

The first aha! was the premise that health, and weight loss, is about so much more than just diet-exercise. It is also much to do with the mind, and with sleep. Working with my own mind has been a deeply rewarding journey, with ahas! around every corner.

A very big aha! was the day a lightbulb went off in my head, and I experientially understood that Yoga is Not a Workout.

Specifically, I understood that the practices of yoga enabled me to access myself.

Yes, just like you’d access files on your computer. If that sounds weird, it’s not meant to be; because it is actually very simple. We are trained from birth to be compliant members of the external world, and to perform in that external world. We are not taught how to access our internal worlds. We are not taught that the internal world is just as rich, mighty, wondrous and powerful as the external one. Brahmanda pindanda as the Sanskrit saying goes: as is the macroscosm, so is the microcosm; what is without is within, and what is within is without. As is the external, so is the internal. The practices of yoga enable one to look within. And it is not merely a vanity pursuit: looking within enables one to live a better external life, and that is the most practical reason for engaging in this pursuit.

The 8 Steps of Yoga (Asanas are the 3rd step)

I must confess that I had always thought yoga = asanas. I had never heard of Ashtanga Yoga, until I met the Himalayan Tradition teachers a few years ago. That’s when I learnt that Ashtanga Yoga consists of the 8 steps – Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Dharana, Dhyana & Samadhi. And that the goal of yoga is Chitta Vritti Nirodha, or the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind. But that is a story for another day.

So, we start our practice of Yoga with the Yamas and the Niyamas. The Yamas are satya (truth), ahimsa (non-violence), asteya (non-stealing), aparigraha (non-covetousness) and brahmacharya (celibacy, a much-misunderstood word, which I want to talk about today).

Remember, we start with ourselves. So, for example, Satya could mean telling the truth to oneself. Being truthful to oneself. Speaking one’s own truth. Being authentic, to use an oft bandied about phrase, today. So, being authentic isn’t new-age. It is the most ancient of ancient practices, the first step in Ashtanga Yoga. Who woulda thunk 😊

The Niyamas are shaucha (cleanliness), santosha (contentment), tapa (penance/burning/pushing oneself gently outside comfort zone), swadhyaya, and ishwara pranidhana. We will cover these later.

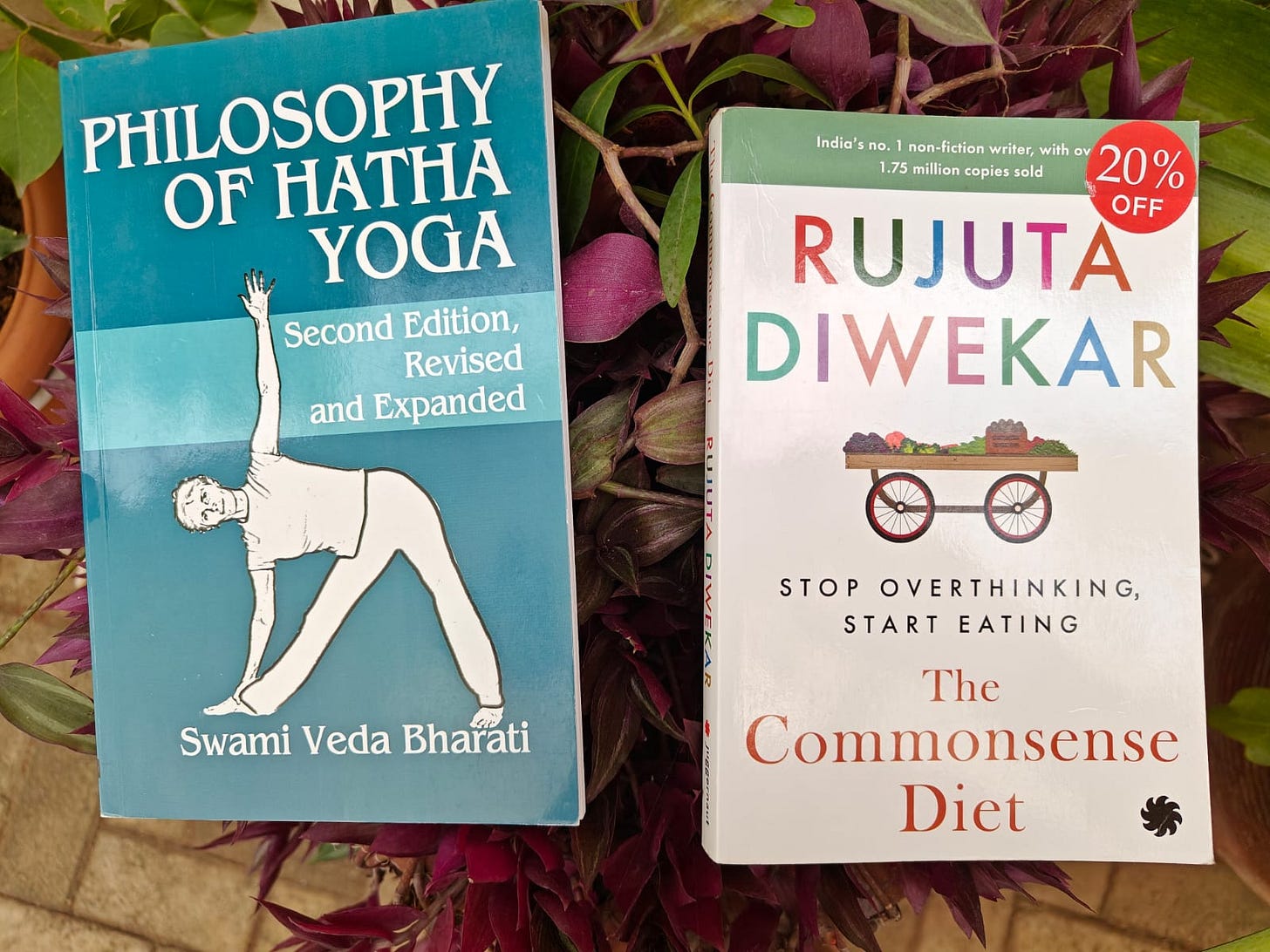

What the works of Swami Veda Bharati and Rujuta Diwekar have in common

Today I want to talk about a wonderful, slim little volume (less than a 100 pages long) called The Philosophy of Hatha Yoga by Usharbudh Arya, or Swami Veda Bharati (SVB) as he was later known.

There are many reasons I love the way SVB writes. A learned Sanskrit scholar, he has a way of making the beauty of the language accessible, and convey a sense of wonder, to utter laypeople like me. (I studied Sanskrit for 3 years in high school because it was supposed to be a ‘scoring’ language. And indeed I scored some 123/125 in the board exam.) He also has a way of throwing in pithy metaphors, sly humour and is able to pull the reader’s leg, entertaining and educating the reader at the same time. That’s a style I love, because it keeps you engaged and makes sure the lesson also sticks.

‘Hatha’ is a very interesting word. I recently discovered the correct pronunciation of the ‘tha’ is a hard t (think ‘t’ as in ‘temper,’ not as in ‘then.’) In Kannada, my mother tongue, hatha literally means a tantrum. If a child is throwing a fit demanding candy, we’d say ‘thumba hatha madthaide magu’ – literally, the child is doing a lot of hatha.

In Chapter 1, SVB says: Most people practise hatha yoga not for its philosophy but for its physical benefits. Their attention is limited to the outer container rather than the inner content of personality. In actual history, however, the hatha exercises were developed within the framework of Ashtanga Yoga, the Yoga of the Eight Limbs, and were meant to train the disciple for higher, deeper, spiritual disciplines.

The human personality exists and functions on manifold levels, and because of this, the word hatha, like many other Sanskrit words relating to the study of the personality, has multiple meanings. In any philosophical study in the Sanskrit language, we can take a meaning that applies on one level of our understanding, grasp that meaning, master that ground, and then leave it behind. If we rise further, the same word on a second level will convey an entirely different meaning. So, the meaning of the word changes as we progress from ground to ground.

The grossest meaning of the word hatha is force, forcing, doing something forcibly, because initially hatha is almost forcing ourselves to break a body habit. If, for example, the body has the habit of slouching, forcing that habit out and forcing a new habit in is hatha.

But it is a gentle forcing. It is not the forcing like that of a wrestler or a weightlifter. So, when one begins to understand from where that gentle part of the forcing comes, the meaning of hatha shifts and then one is thinking not of the physical body alone but of subtler truths, cosmic truths, the universal energy fields, the sun and the moon. The word ha means the sun, the word tha means the moon.

As the understanding of one’s personal, physical relationship with the universe begins to dawn, again the meaning shifts, and the sun is not the sun that rises at six o clock in the morning, and the moon is not the moon that shines in the sky at night. The sun is the active, masculine right nostril breath and the moon is the intuitive, feminine, left nostril breath. In this way, one finds that the practice of hatha yoga is working simultaneously on various levels.

SVB says of the yama of celibacy, with a practical example: the recommendation is that when you are eating, enjoy the food at that time, and do not crave it at other times. That is true celibacy. It is not that a person refuses to speak when his tongue itches to talk, but that the tongue no longer wishes to speak. And when the person does speak, it is no more than absolutely necessary, and it is beneficial and pleasant to people. That is celibacy. Celibacy is the mind not craving too much. (p 80)

It is good to have satvik food, but better still to have a satvik disposition while eating it. (p. 50)

Let’s read that again: the recommendation is that when you are eating, enjoy the food at that time, and do not crave it at other times.

There’s so much one can unpack about emotional eating from these few lines. Research shows that there is a lot of ‘food noise’ that goes on in the minds of the obese, i.e., they are constantly thinking about what they are going to eat next. In the minds of the dieters, this takes on additional nuances. When I was doing Intermittent Fasting, I’d constantly be thinking about food and looking at the clock. And I would end up bingeing. While one is eating, there is guilt. Being very good all day and then going on a bender at midnight. Been there, done that.

So, practice true brahmacharya of food: eat well and enjoy with all the senses when one is eating. And when one is not eating, do not think of food, fantasise about food, or eat when one is not hungry.

The Commonsense Diet – Rule of 4 and Rule of 4Ss

I have become a fan of Rujuta Diwekar’s work of late. RD is also very obviously into yoga and yoga philosophy, she gives us little teasers here and there. She says, practice the rule of 4:

Step 1 – Visualise how much you want to eat

Step 2 – serve yourself half that amount

Step 3 – take double the amount of time you would normally take, to eat it

Step 4 – if you are still hungry, repeat the steps all over again.

Start slowly, try to practise this with one meal a day.

When you are eating, start with the rule of 4Ss:

1. Sit,

2. Still,

3. Silently,

4. Use all the senses to eat.

They sound very simple, but like anything profound, they are not easy. Simple, not easy.

Have you ever had a meal in silence?

I never did. Growing up in a large family, mealtimes were always fun, full of laughter, banter, kidding around, exchanging news and stories of how our day had been, and so on. And there is nothing wrong with that. The sharing of food is how we share love, and that has been the case since time immemorial.

What’s crept up on us insidiously are gadgets. In many families, mealtimes are now had in the presence of the TV. If not the TV, then it’s the phones that provide company while eating.

The first time I had a meal in silence was at a wellness retreat in Pune. It was one of the hardest things I have ever done. My instinct when I sit down to a meal is to first think of a nice conversation-opener, take an interest in the people around the table with me. Somewhere I felt it is also expected of me. So, to curb all those instincts, the ones that want to talk and laugh at mealtimes, was extremely hard. But once I got the hang of it, it became surprisingly satisfying.

Try it sometime. Can you eat one meal in silence, with no gadgets near you? and no talking?

The Secret of Satiety

What happens when one sits still and silently, is that the senses can be engaged to fully enjoy, relish and derive immense satisfaction from the food one is eating. When I first tried this trick, I felt so sated with one medium-sized rava idly and onion-potato sagu, that I didn’t feel like going back for a second one at all.

This is what SVB is saying when he says, when you are eating, eat fully. And when you are not eating, don’t fantasise about food!

Who knew that this is what Brahmacharya actually meant...!

So, this World Yoga Day – by all means, enjoy doing asanas. But also see, can you practise one of the Yamas or Niyamas?

Can you, maybe, eat a meal in silence, looking at, smelling, tasting, slowly chewing and actually relishing your food?

What was the experience like?